Safe and efficient storage of samples—whether chemical, biological, or clinical—is an integral, yet sometimes overlooked, part of laboratory work from drug discovery to clinical trials. The goal is straightforward: faithfully preserve materials for later use or analysis. The execution can be notably trickier, especially as collections grow and the tracking and movement of samples becomes more complex1. Risks and inefficiencies in a storage strategy can undermine the value of an entire sample collection. Many samples cannot be replaced without great effort or time, if at all. Compromising their physical integrity or associated data can have detrimental impacts on research and patient health.

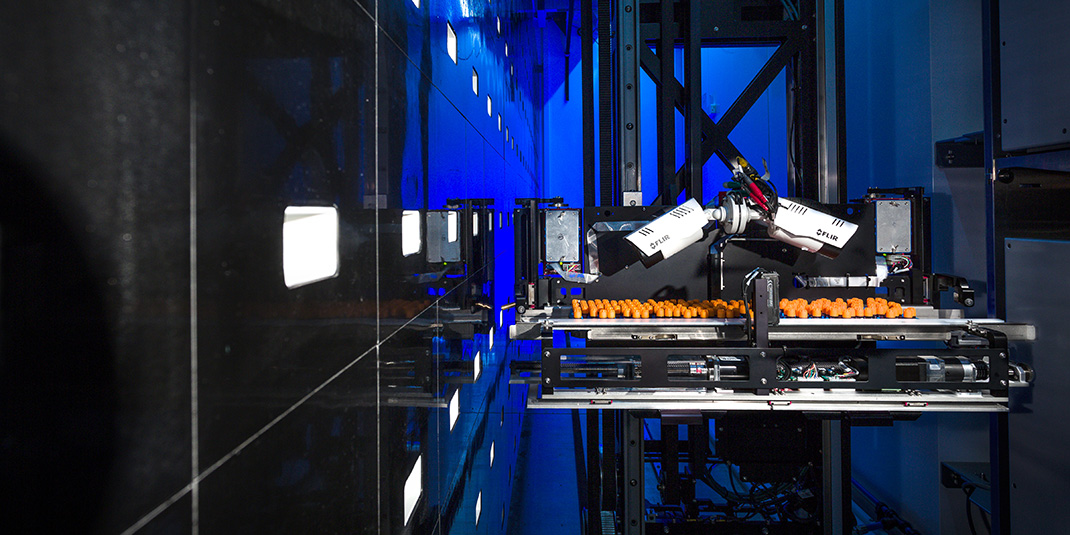

Approaches to sample storage can be broadly categorized as manual or automated. Manual workflows are the simplest and cheapest to deploy. They typically involve use of freezers (or refrigerators) containing multiple racks of boxes. To retrieve samples, users must wear protective equipment, open freezer doors, pull racks, and remove the target samples. Automated workflows, on the other hand, use robotics to locate and move samples within a cold storage unit. Samples are delivered to the user with minimal input. While the differences between the two strategies may appear strictly mechanical, they have far-reaching consequences for sample quality, resource utilization, and collection management. Let’s examine each factor in more depth.

Automated sample storage better protects sample quality

Assays are highly dependent on the quality of the input materials. “Garbage in, garbage out” is a popular aphorism that sums up the consequences of poor sample quality. Once harvested, biological materials are immediately subject to degradation and stress-induced changes. Critical reagents can break down or undergo chemical modification over time. Proper storage conditions inhibit these processes to preserve the original state of the material. Cooling is central to this effort, as it effectively reduces the rate of all chemical activity. Long-term storage of most biological samples requires temperatures of -20°C to below -135°C, the glass transition temperature of water (Tg) and the point where enzymatic activity is believed to cease. Temperature fluctuations can have a detrimental effect on biospecimen quality—including enhanced degradation, reduced cell viability, and altered gene expression2-4.

Transient Warming

Cold storage units are responsible for maintaining a consistent temperature range, but they are not without risk. Samples may be exposed to harmful temperatures due to critical failures—such as power outages and equipment malfunction—or more commonly, transient warming events. When freezer doors are opened and materials are removed, both target samples and non-target (innocent) samples experience warming. The rate and extent of this warming depends greatly on how the task is performed and the temperature difference between storage and picking environments.

Consider retrieving samples from a cryogenic liquid nitrogen (LN2) freezer using manual and automated workflows. Pulling racks by hand to locate the target box exposes the entire rack to ambient conditions, increasing the risk of degradation to innocent samples. Unlike a human, robotics can locate and select samples at very low temperatures within the cold storage unit, creating a much more controlled environment for retrieval5. Testing shows that samples warm faster (~4X) and are exposed to temperatures above Tg longer (~2X) in a manual process compared to an automated one (Table 1). Consequently, automation significantly lowers the risk of damage caused by transient warming.

Table 1. Comparison of methods to retrieve samples from a LN2 freezer

| Manual LN2 Freezer | Automated Systema | |

|---|---|---|

| Time to find and remove box | 120s | 30 – 90s |

| Time rack is outside LN2 environment | 30 – 120s | 15 – 30s |

| Rate of warming in first 30 s outside LN2 environment | 0.23°C/s | 0.06°C/s |

| Average time for innocent samples to warm to Tgb | 126 | 258 |

a The CryoArc™ -190°C LN2-Based Automated System was tested.

b The glass transition of water (Tg) is -135°C. LN2 freezers maintain a storage temperature of -150°C to -190°C.

Reproducibility

Manual workflows not only expose samples to longer and larger temperature fluctuations but also are inherently more variable, compared to an automated system. Speed and technique vary between users and even within an individual over multiple performances. Handling errors further increase the risk to sample quality: pulling incorrect samples, misplacing materials, improperly securing doors, and dropping racks/boxes delay retrieval and increase warming for target and innocent samples. In addition, samples stored in a manual -80°C or LN2 freezer experience different temperature swings and warming rates depending on their shelf or rack position5,6. All these sources of variability, which only worsen with longer storage duration, can lead to major reproducibility issues in downstream experiments and applications.

In contrast, an automated system is highly consistent when removing and adding samples to the collection and is designed with features to minimize warming of target and innocent samples. Simply put, a robot outmatches a human for sample picking in terms of reproducibility, especially as the size and utilization rate of the collection increases.

Save resources with automated sample storage

One major advantage for manual freezers is initial cost. Automated systems are more expensive—often by a large margin—than their manual counterparts. However, to calculate the true cost of a sample storage strategy, we must take a more holistic and longer-term view, as operational expenses differ significantly between the two strategies.

Labor

Manual storage requires staff to spend time moving samples into and out of freezers as well as updating the inventory records. Labor costs add up quickly as the size and utilization rate of a collection increase. For example, a manual approach would require six additional full-time employees at a cost of approximately $324,000 per year to manage a collection of two million samples with 40% utilization annually, compared to an automated workflow (Table 2). Automation can reallocate personnel and budget toward other important and less rote functions.

Table 2. Estimated labor costs for sample management

| Collection | Manual | Automated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of samples | 2,000,000 | ||

| Utilization rate | 40% annually | ||

| Annual picks | 800,000 | ||

| Picks per daya | 3,200 | ||

| Pick rate | 500 per person per shift | >4,000 per dayb | |

| Full-time employees required | 7 | 1 | |

| Total annual labor costsc | $378,000 | $54,000 |

a Assumes 250 business days per year.

b Based on the BioArc -80°C Automated Sample Storage System.

c Based on an average total pay of $54,000 for a sample management technician in the US (Source: Glassdoor).

Space

Automated systems are generally more space efficient than manual freezers, with space savings up to over 30% (Table 3). They can store samples with higher density and thus have a smaller footprint. Also, conventional freezers usually require more room around the unit to allow sufficient air circulation and clearance for freezer doors.

Table 3. Floorspace needed for manual and automated storage

| Collection | Manual | Automated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of samples | 2,000,000 | ||

| Utilization rate | 46 | 1 | |

| Floorspace per unit | 3.7m2 (40ft2) |

90-120m2 (969-1292ft2) |

|

| Total floorspace | 170m2 (1,830ft2) |

90-120m2 (969-1292ft2) |

a Based on a typical ultra-low temperature upright freezer.

b Based on the BioArc -80°C Automated Sample Storage System. Exact dimensions depend on the specific configuration.

c Assumes 1.9ml sample tubes stores at ≤90% capacity.

Energy

When opened, conventional freezer doors allow a large amount of heat to enter the unit, which then must be removed by the cooling system. This process is very energy-intensive, especially for ultra-low temperature freezers. As discussed above, automated systems are better at shielding innocent samples from temperature fluctuations during picking. This not only protects sample quality but also reduces the amount of cooling needed and energy consumed. The extra cooling demand on conventional freezers degrades their compressors faster, resulting in greater power consumption over time and a shorter shelf life compared to automated systems7. Thus, overall power usage is lower for automated storage, lowering both running costs and the carbon footprint.

Automation streamlines sample management

Managing a sample collection is both a physical and informational undertaking. For the latter, samples must be documented, assigned locations in storage, and logged over time. Manual efforts at inventory control using basic tools like spreadsheets are cumbersome when a collection grows into the thousands. They also are prone to human error and negligence—such as inaccuracies in documentation, poor sample tracking, and deviations from standard procedures—that can lead to delays, under-utilization of the collection, and regulatory violations. These issues only worsen with larger teams and personnel changes.

Automated storage, on the other hand, streamlines many of the tedious and complicated aspects of inventory management. Built-in software enables real-time visibility, comprehensive event tracking, and convenience – such as remote access and integration with a laboratory information management system (LIMS). The processes of sample addition and removal are more controlled and simplified, especially when the system can automatically scan and register barcode-labeled labware. All transactions are automatically logged, promoting better compliance and traceability. Audit trails and cold chain of custody records are substantially easier to generate and, importantly, are more accurate and thorough than those created by hand. For regulated environments, automated systems can be designed with 21 CFR Part 11 compliance in mind. Administrators can also add greater security to the collection by managing access via user-defined controls.

Conclusion

The benefits of automating sample storage are manifold, including highly reliable protection of sample quality, low running costs, and simplified sample management. Automation is not required for every collection, but at a certain size, manual methods will likely become too inefficient and prone to too much risk, threatening the long-term value of the entire collection.

References

1. Burton, M. S. The Science of Sample Management: Enabling Discovery from Bench to Clinic. SLAS Technology: Translating Life Sciences Innovation vol. 24 243–244 (2019).

2. Shabihkhani, M. et al. The procurement, storage, and quality assurance of frozen blood and tissue biospecimens in pathology, biorepository, and biobank settings. Clinical Biochemistry vol. 47 258–266 (2014).

3. The Effect of Storage Temperature and Repetitive Temperature Cycling: On the Post Thaw Functionality of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Azenta Life Sciences White Paper (2016). https://www.azenta.com/resources/effect-storage-temperature-and-repetitive-temperature-cycling-post-thaw-functionality

4. Yang, J. et al. The effects of storage temperature on PBMC gene expression. BMC Immunology vol. 17 (2016).

5. Sample Warming During Innocent Exposures From an LN2 Freezer: Comparing Temperature, Time & Workflow Using Manual vs. Automated Systems. Azenta Life Sciences White Paper (2015). https://www.azenta.com/resources/sample-warming-during-innocent-exposures-ln2-freezer-comparing-temperature-time-workflow

6. Is Your Biobank Healthy? Automated Storage Refrigeration vs. Manual ULT Technology. Azenta Life Sciences White Paper (2019). https://azenta.com/resources/your-biobank-healthy-automated-storage-refrigeration-vs-manual-ult-technology

7. Gumapas, L. A. M. & Simons, G. Factors affecting the performance, energy consumption, and carbon footprint for ultra low temperature freezers: case study at the National Institutes of Health. World Review of Science, Technology and Sust. Development vol. 10 129-141 (2013).